By Joe Gibson

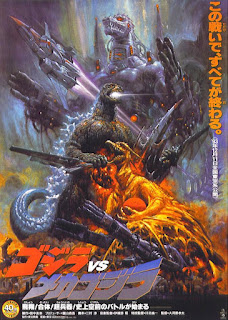

To celebrate Godzilla

Day 2024, I started a review of Godzilla vs Mechagodzilla II, but it turned out

to be too long for a reasonable single post. You can read the first part here: https://planninecrunch.blogspot.com/2024/11/godzilla-vs-mechagodzilla-ii-strengths.html

In that first part, I

discussed a broad view of the history leading up and extending beyond Godzilla

vs Mechagodzilla II, because the context is very important for a film at one

point intended to be a finale and regardless, this film did shift the

trajectory of the Heisei series by making the moments of sympathy for Godzilla

in the previous films amount to a greater payoff. Then, I began to work my way

through the film’s plot, doing my best to analyze each plot point. We left off

on Godzilla beginning a rampage while the main characters were gathered around

the newly birthed (via pteranodon nest) Baby Godzilla.

Chapter 2 (Plot

Run-through) Continued

Mechagodzilla is

launched to intercept Godzilla, and if this seems too early for the title fight

at only 30 minutes in, it is, I was serious about the 27 minutes of Godzilla

screen time. Not only do we get a Godzilla vs Rodan warm up match but Godzilla

and Mechagodzilla get at least two rounds too. The G Force Commander refers to

Aoki as a jackass for not showing up, so they get a backup pilot. At this

point, Mechagodzilla is in the hero role. Godzilla is an established menace,

and Mechagodzilla is the weapon of the virtuous organization to defeat him,

representing no threat to the innocent (just as Godzilla seems to be of no

benefit to the innocent). The film even casts Mechagodzilla in a bright light

just to make sure we are on the same page that it is definitely the good guy.

This fight plays out

mostly as a weapons display for Mechagodzilla, with the rainbow megabuster

mouth beam and plasma grenade belly button port that actually knocks Godzilla

down from absorbing and redirecting his energy (reminder, this only works because of the aforementioned diamond plating). Mechagodzilla fires paralyzing

missiles into Godzilla and another shot of the plasma grenade to prep the shock

anchor, essentially a really big taser.

It seems as if

Mechagodzilla has Godzilla dead to rights, but, if you’ve been paying attention

to the Heisei series, you know that Godzilla does his best fighting to get back

up off his back and even exactly how he will get back up. Whenever Godzilla’s

mouth starts foaming, he is liable to release a nuclear pulse or else redirect

energy, and giving him a literal direct line to overcharge you is never a good

idea. Godzilla knocks over Mechagodzilla, and we learn where his rampage will

take him: Kyoto, where the Baby is. Whenever I think of Heisei Godzilla rampage

and evacuation scenes, I think of the montage as Godzilla finds his way to

Kyoto.

The four main humans and

Baby Godzilla go to a deeper secure level of the building they are in, and the

characters conclude Baby Godzilla has been calling Godzilla to him and that

Godzilla also went to the island in the first place solely for the Baby.

Godzilla is a little bit too destructive trying to get into the building,

scaring Baby Godzilla, and this causes Godzilla to leave, very suddenly and

dejected, even avoiding other buildings on the way out, which is very interesting

(it would be more understandable if Godzilla reacted to disappointment by

destroying those buildings, but it seems the rampage is over from the moment

Baby does not want to leave with him).

Aoki, when chastised by

the G Force commander for not being there when Godzilla attacks, tells him he

used up some vacation time he had coming for him. It is very important that you

understand that Aoki is a lackadaisical anarchistic free spirit that would

rather crack a joke in the face of authority than honestly explain the major

contribution he has made to their Godzilla research by being the only reason

Baby Godzilla was born, because it is not a contrivance but a consistent

character trait. Aoki only cares about pteranodons, and, as the only organic

one in this film is presently dead, he will try to resurrect his robotic ones

going forward. The commander is uncharacteristically peaceful during this

exchange, and it turns out that is because he is reassigning him to parking lot

duty.

While this is all

happening, Azusa has become more comfortable with her role as the young

Godzillasaur (affectionately called Baby)’s caretaker, as he begs her for a

hamburger (the camera does not focus on burger as she does something to it

before giving it to him, making it possible she removed the meat patty) on the

way to their new enclosure within G Force. The G Force officials overseeing

this refer to Baby only as a very important animal, and we learn why a few

minutes later. Baby contains a nerve cluster/second brain near his back, and

they intend to target that point on Godzilla (once more the juxtaposition of

this innocent creature in captivity being Godzilla but also the key to his

downfall.

Dr Asimov is the

obligatory English speaker (though the actor is Italian) in a Heisei Godzilla

movie, overseeing the Mechagodzilla project, and Aoki traps him in the parking

garage in order to convince him to reinstate Garuda as an official part of the

Mechagodzilla project to “increase Mechagodzilla’s maneuverability.” A computer

simulation shows us a mockup of Garuda’s functionality, and Asimov agrees they

can make it so that Garuda can attach to Mechagodzilla when needed in combat.

Baby is mischievous in

captivity, and Aoki visits to hit on a more receptive Azusa by showing off his

small personal flight vehicle the Pteranodon. This scene is subject to many

memes and much ire as he wins her over by flying around stupidly and

irresponsibly on a pteranodon robot for little to no reason other than that he

(or at least someone on the creative team) wanted it to be so. In my analysis,

this is yet another example of how much he enforces his will on the plot by

liking pteranodons and yet being unable to have any substantive interaction

with a physical one. People complain that he does not interact with Rodan more,

and, yes, that is weird, but these same people get annoyed by and ignore when his

pteranodon passion trait still influences his key scenes. Another point of

interest is when he, in this same scene, refers to his promotion as being back

to flying again, a way he can be like the pteranodon just like on his dumb two

seater robot.

How Baby Godzilla feels

about anything at any given moment is a little unclear because the suit is not

as clearly defined as the Heisei Godzilla suits and animatronics. He expresses

some fear in situations involving Godzilla and Rodan but usually only when directly

in danger. He is perfectly docile when a robot that somewhat resembles Rodan

flies overhead, and when he shows agitation following the psychic children

singing the plant song and incidentally reviving Rodan, it is not fear and is

instead because the song gives Baby power too. Actually, while we are here, I

am not entirely sure why this time the song was sung, it revived Rodan into

Fire Rodan, but it did not the previous time. The only variable difference is

between that of a recording and a live production of people very high in

psychic energy. Gun to my head, I think that is what the film is going for, but

they should have better expressed that unless I missed something.

G-Force’s plan is to use

the Baby to lure Godzilla to the Ogasawara Islands and have Miki on

Mechagodzilla to psychically locate the second brain for their G-Crusher

attack, and, this is where the dubious morality of G-Force fully comes into

play. Beyond just using the military pieces against the giant monster, G-Force

is now using Baby and Miki, two peaceful innocents, as chess pieces in this

game. Azusa pleads to a UNGCC higher-up that Baby is an intelligent being that

deserves his own life, but the retort is that G-Force’s most important task is

defeating Godzilla no matter the cost. Now, the obvious wrinkle here is that if

G-Force knows Godzilla will follow the baby, that means they can figure out his

only attacks this year have corresponded to the baby, so using the baby under

any circumstances assures Godzilla’s activity, and they really should not have

him anywhere near their main base of operations.

Miki being present at

the meeting of higher up G-Force members might screw with my interpretation of

her and Aoki both being outsiders and sitting together consequently, but she is

still the odd one out, and her input in not only the planning of but

participation in a G-Force mission is meant to be an escalation in story, so I

do not think it damages the earlier plot point. After the meeting, Miki, Aoki

and Azusa all compare notes, pondering that Baby Godzilla was born 65 million

years too late to have a good life…or maybe too early if dinosaurs might come

back as Azusa contemplates.

Baby is loaded into a van in chains and a collar, and his eyes

light up in fear just so that it is clear this is an inhuman animal rights

violation and not just putting a dog in a temporary moving kennel (again the

design is good, but it is very difficult to tell its emotions without the

eyeball lights flashing, something by no means true of Heisei Godzilla, who by

this point has scowled, done a double take and even cried very visibly and

clearly in previous films). Azusa decides to go with him, and Fire Rodan goes

after the container. Rodan’s devotion to protecting his adoptive baby brother

is the most interesting thing that has been done with this character since the

debut film (where he was devoted to his spouse even to the point of dying

together rather than living alone), and I think it speaks to my earlier point

equating the Shin movement with the original Heisei philosophy. This was not

just a different take on Rodan; this was the true and new Rodan after things

got a little out of hand with the superhero with the droopy beak. Omae has been

out of the movie for a little bit, but here he gets to jump to the conclusion

that Baby and Rodan are communicating, despite there being little to suggest

that from his perspective (obviously he is right, but he strains credulity

after a certain amount of omniscient rants unless he too is supposed to be

psychic, which we can just call the Trapper Beasley Effect, see my Godzilla x

Kong review for more information: https://youtu.be/AI_FMxtTlIk?si=EA51lODIQp2LUVr1).

Miki hesitates to put on

her special helmet, once again driving home that the Heisei series’ main

character and otherwise moral center is not fully in this fight. Aoki is all in

but for different reasons, as he informs the G-Force commander that he built

Garuda and has to see it through (but we must also remember Azusa was literally

just kidnapped by Rodan, so that is an additional two incentives for him to fly

out to meet them).

Rodan circles and finds

a place to land. His red Fire Rodan coloring stands out against the night

backdrop. (Whether or not Rodan standing out against a dark backdrop is

intentional, it is still interesting that back when this conflict was clearer,

Mechagodzilla was the shining hero with a gleaming background, but this fight

will take no such opportunity to make Mechagodzilla look so good. Mechagodzilla

will even lose an eye to Rodan and consequently look somewhat sinister and at least

less human). Rodan opens the container, and Baby screeches (or yawns, his eyes

aren’t red). Mechagodzilla and Rodan finally square off, and Rodan immediately

fires a purple heat beam (this was the Heisei era after all). Mechagodzilla

preps the plasma grenade, but the commander places his trust in Aoki to

distract Rodan first. I would have liked more scenes between them to justify

this turn, but it is still cathartic to see Aoki finally taken seriously after

he has stepped up to help out.

Aoki flies around and

attacks Rodan, siccing the pteranodon on himself. Rodan’s air superiority

knocks him out of the sky, and the commander is actually displeased to see this

happen to Aoki. The plasma grenade knocks Fire Rodan into a tall building, and

Mechagodzilla slowly approaches him to finish the job, more of a slasher

villain than good guy in presentation. Rodan does the aforementioned eye

pecking but gets blasted and starts to bleed out and foam at the mouth.

Mechagodzilla approaches again, even more sinister looking than before. I

forgot Omae was here for the climax, but he arrives to try and get Azusa out of

the container just as Godzilla pulls up.

A UNGCC official

comments that Godzilla is there at last, and here is a point of hypocrisy on

their part. This fight is not happening on the uninhabited Ogasawara Islands,

per the plan, and Mechagodzilla has already caused considerable collateral

damage by blasting Rodan into the tallest building there. Continuing the plan

to exterminate Rodan and Godzilla here rather than move the now unguarded

container to the aforementioned islands represents a rather huge moral

compromise that G-Force and the UNGCC made unflinchingly. If you think I am

reading too deep into this, then explain why the G-Force commander hesitates

before launching into this attack. However, there is still a great deal of

complexity here as Mechagodzilla is still the underdog for having lost the

previous fight, and Godzilla immediately shows off his strength by lifting

Mechagodzilla and throwing him. Similarly to earlier, Godzilla’s focus is not

the buildings, but he is just so physically impressive that he is a constant

threat.

Aoki leaps back into

action to attack Godzilla to buy the Mechagodzilla crew time to right

themselves, and the commander and Aoki have genuinely nice banter as Garuda

joins up with Mechagodzilla to share weapons and energy systems to become Super

Mechagodzilla. Super Mechagodzilla has all of the weapons of both mechs and

releases them as a barrage on Godzilla. This is something the Showa

Mechagodzilla as a villain did in his two movies, and Super Mechagodzilla hides

behind buildings to evade Godzilla’s beams. The two opponents roar quite a bit

at the start of this scene, so I want to highlight that Mechagodzilla has a

roar, which is quite strange taken any way other than symbolically. Its roar is

uncanny, an artificial imitation of Godzilla’s, an easy way to communicate it

is unnatural. Super Mechagodzilla finally prepares the G-Crusher, and the UNGCC

brass pressure Miki into targeting Godzilla’s second brain, something she

clearly does not want to do.

The G-Crusher discharges

electric pulses to Godzilla’s second brain, paralyzing him. Whether or not we

should consider this a death for the character is unclear. Previous drafts had

Godzilla die here, and, if we compare Godzilla to Rodan, Rodan died a couple

days ago but was able to revive and is currently bleeding out. My point is that

these are death scenarios that are not permanent, thereby meant to leverage our

sympathy more so than denote the end of a character.

With Godzilla defeated,

Aoki ditches Super Mechagodzilla to go help Azusa. The commander looks very

solemn during this, and Aoki clearly cares more about Azusa, so at this point,

Super Mechagodzilla the entity is no longer on our side as the audience. Super

Mechagodzilla continues to pelt Godzilla with every attack it has, and Baby

cries in sadness at Godzilla’s impending death. This inspires Rodan to circle

back, and Super Mechagodzilla shoots him out of the sky. But Rodan lands

on Godzilla and sacrifices his life and essence to give Godzilla the radiation

he needs to heal his second brain. Rodan was once again so devoted to his

family that he sacrificed himself, and this moment is one of my favorites in

the entire Heisei series.

Because of the new

energy, Godzilla is able to melt that diamond plating we had all film building

up to, so Godzilla unleashes his new Red Spiral heat Ray to destroy Super

Mechagodzilla. As I compared the diamond plating to the BEAST Glove, here is

the ultimate third-act payoff. After it has worked thus far across the film and

is based on past technology, it ultimately fails as a cathartic moment, which I

find to be an apt comparison to the BEAST Glove, which had some setup but no

relevance until it worked flawlessly even when it should not have (see the

third part of my Godzilla x Kong review for more information).

Godzilla’s Red Spiral

Ray overpowers Super Mechagodzilla in a beam clash and knocks over the mech.

Red flames akin to hellfire engulf Super Mechagodzilla, and the robotic

operating system of Mechagodzilla claims there are no survivors when really

there were no casualties. I did not highlight it yet, but there has been a

minor theme in this film about how unreliable technology is compared to

organic. Mechagodzilla breaks down and only has a finite amount of energy even

when Garuda joins with, but the familial power Baby Godzilla and Rodan share is

enough to fuel Godzilla when he breaks down. The pteranodon robot also breaks

down abruptly, and Rodan can easily beat Garuda in a fair fight. Artificial

life truly is lesser than organic throughout this entire film.

After a tearful goodbye,

Azusa bids Baby go with Godzilla, and Godzilla tries to convince the kid to

leave him with him, but Baby is scared suddenly, and Azusa asks Miki to

ask Godzilla to take the Baby with his telepathy. This is stupid, because

Godzilla clearly is on that same page, and it is Baby Godzilla that stands in

the way of this. Miki realizes this, and the film’s editing shows us that she

alleviates Baby Godzilla’s fear rather than communicate with Godzilla

(honestly, this was probably a mistake of the dub, but also, speaking

practically Godzilla probably knows that Miki is the one that just killed him,

so negotiating with him is unwise).

As Godzilla and Baby

walk off into the ocean together, the commander and Mechagodzilla team

pontificate about the differences between life and artificial life. This is a

common criticism of the movie, but I have already argued it portrays this. My

only issue is that the commander was not present for all or even necessarily

most of the showings of the tenacity of natural life. Yet more controversial is

Aoki and Azusa speculating that a dinosaur age awaits. I have heard a lot of

complaints about how the film does not really justify or earn this dialogue

with any profundity, but that is really not the point. This is how Aoki and

Azusa as they have been written thus far would reflect on these events, so it

is an example of good writing, and if your analysis does not even allow for

character consistency as an option for a creative choice you do not understand,

then I do not think you are putting enough thought into your analysis. I am not

perfect in this, but I always try to approach a film with its due respect and

meet it within what it aims to say and how. I guess I just want to ask how we

ruled out that the film is just merely keeping consistent with established

character traits rather than rushing a plot development we did not see.

Unfortunately, I'll have to end this part here (at least we finished the film this time). Throughout this review, I've highlighted some key concepts whenever they appeared in this film, and, next time, I will bring this all together for some commentary on the thematic content I see in this film and what conclusions I draw based on these scenes. Stay tuned for the final part soon.