By Joe Gibson

Hi, and welcome back to

Plan9Crunch’s review of Godzilla vs Mechagodzilla II. In the two previous parts

(linked below), we went over an introduction of the context for Godzilla vs

Mechagodzilla II and a plot runthrough. As we are now discussing and concluding

on thematic content, this will make a lot more sense if you have read the

previous parts.

https://planninecrunch.blogspot.com/2024/11/godzilla-vs-mechagodzilla-ii-strengths.html

https://planninecrunch.blogspot.com/2024/11/part-two-godzilla-vs-mechagodzilla-ii.html

Chapter

Three - Moral Befuddlement or The Trolley Problem of Young Baby Godzilla

Based on what we just

went over, I would summarize the themes of this film as intentionally confused

and confusing. Our desired allegiances are unclear, because Mechagodzilla is an

iconic villain now reimagined as an extension of human desires, while Godzilla

(hero or villain that he can be) is finally acting on the sympathetic moments

trickled within this Heisei chronology in order to step up as a slightly

redeemed version of this character. Throughout all this is sparse commentary on

life vs artificial life and responsibility vs self-interest.

Kazuma Aoki is an

annoying, irresponsible, flaky, obsessed and pushy idiot with a stupid flying

pteranodon robot, and half of the reviews I see of this movie focus on that,

but the other half detail how he is a singularly relatable and funny character.

Imagine for a moment growing up in the 70s, 80s and pre Jurassic Park 90s being

a fan of dinosaurs or Godzilla, when the collective conscious reaction is to

dismiss those things as dumb. Aoki’s passions lead him to court an attractive

successful woman and be the hero without having to directly kill a monster but

fighting both. Many viewers see themselves in him, and I think that is

intentional when you contrast him with the well-intentioned but misguided

officers and contractors of G Force, best exemplified through returning star

Miki Saegusa choosing this film to realize killing Godzilla is not a simple

noble thought anymore or the stern G Force commander softening up to Aoki.

One of the biggest

complaints against this film is that its Mechagodzilla lacks a personality

compared to the 70s one, and that is, I think, a benefit to the writing rather

than a drawback. Mechagodzilla, in this film, is not a character, but a very

glorified tank, with the thicker monochromatic design with sleek curves and

bleeding-edge technology supporting this interpretation. Godzilla is the

personality to focus on in this story; Mechagodzilla’s role in this story is to

oppose and contrast Godzilla.

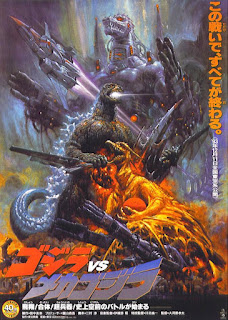

In the hand-drawn poster

for this film, Mechagodzilla is this hulking ugly menace over Godzilla and

Rodan having inflicted gory injuries on them, and no such scene occurs, but it

is representative of the power and morality shift that happens in act 3. A very

popular format for stories involves the hero winning against the rival, losing

against the villain and then getting the rival’s help to beat the villain, but

this is also a very flexible format. Rocky III has Rocky beating Apollo as the

intro backstory to spend more time on why Rocky then loses to Clubber Lang and

how Apollo will help Rocky win, while Black Panther plays it more straight

structurally (T’Challa beats M’Baku, Killmonger beats T’Challa, M’Baku supports

T’Challa’s attack on Killmonger). This films holds off on Godzilla being the

hero or even losing until the third act, giving Rodan more agency as a

character than M’Baku and Apollo due to less screen time with Godzilla, and

also assigning this persistent growing sense of dread that we do not know where

to assign until Super Mechagodzilla starts acting like Showa Mechagodzilla.

Now this also raises a

question. Who should we blame for Super Mechagodzilla’s ferocity: the mech

itself, the pilots therein or the people giving the orders, and doesn’t that

sound awfully familiar for a series originally existing to comment on

destructive actions taken to end a war? Most other reviews I have seen for this

film would have me believing I am seeing subtext that is not there, but again I

return to what I said earlier. Where is the analysis that officially ruled this

out and decided it was just a dumb light show? I am by no means the final say

here, and, if I am wrong, please show me when and where and by how much. This

movie still holds up as a mostly consistent popcorn flick, and Mechagodzilla’s

design and purpose can be praised for subjective preference if not thematic

content, but I genuinely see an attempt at brilliance here.

Heisei Rodan is my

favorite incarnation of the character, despite the fact that he started the

annoying trend of Rodan being smaller and weaker than Godzilla, so there is

some degree of bias I hold in approaching this part of the analysis. I

appreciate the design erring closer to Pteranodon than a winged guy in suit design, and I really like the three horns (as opposed to the usual two) and face

equal parts ferocious and sympathetic depending on the scene. Because

Mechagodzilla is a more long range then melee opponent, Rodan’s fight with

Godzilla gives us the best tooth and claw action in the film, so I also

appreciate that. But I also find his use very interesting in a way that ties

into the tag team match of Godzilla x Kong: Godzilla and Kong vs a shadow

Godzilla and a shadow Kong, Godzilla and Rodan vs Mechagodzilla and

Mecha-Rodan??

Garuda is very

interesting in this movie, designed mostly to mirror Rodan, as, in the climax,

Garuda must join with Mechagodzilla to win, and Rodan must join with Godzilla

to win. Aoki is no longer piloting Garuda at that point, just as Rodan

sacrifices his mind and body to fuse with Godzilla. Aoki’s agency is often

overlooked in this story, but he decided to name his anti-Godzilla weapon after

a bird god that is the enemy to all snakes in folklore, and Garuda as a modern

cryptid is speculated to be surviving pteranodon same as Mothman, Thunderbird,

Batsquatch, etc, so Rodan = Garuda is by no means an absurd talking point.

(Also, while Aoki only interacts with Rodan adversarially, he really does not

get the option to study Rodan, and arguably does a lot of what he does because

of that, as I have already detailed.) I am not claiming it the richest

subtextual layer in any film, but if we are giving this film the fairest shake

possible, it deserves mention especially in view of what the film builds to

with these ideas. If you doubt that Garuda joining with Mechagodzilla is an

intentional thematic element to these characters, then you should recall that

Garuda is the mount to Vishnu, inherently tied to a more powerful character.

Before I summarize my

thoughts on Godzilla in this movie, I think it is wise to briefly compare this

film to 1967’s Son of Godzilla, since many of the same building blocks exist in

both. Godzilla’s redemption arc started sooner than Son of Godzilla in the

Showa series, but there was a sort of unease in the mid Showa entries toward

Godzilla (the humans willingly dump him and Rodan on Planet X in Godzilla vs

Monster Zero, and he is merely the better of two bad options in Ebirah: Horror

of the Deep) leading to a film where Godzilla is just on an island fighting

villainous mutation monsters to protect a child, and the next time we see him

after this, everybody knows he’s a hero. But, in terms of aforementioned

similarities, Goro Maki (the Akira Kubo version in SoG, not the Ken Tanaka

version from Godzilla 1984) is a campy and comedic journalist who pushes

himself into dangerous situations out of genuine interest that annoys the

people around him and wins over the girl, while Aoki is all of those things

except a journalist. Rodan also slots into the Kamacuras role as a lesser kaiju

killed by Godzilla at the beginning that also gets to the fight the villain

monster at the end, be it spider Kumonga or Mechagodzilla (let it be said that

Kamacuras’ puppetry is far more impressive). And then, of course, the female

lead that serves as partial caretaker to the Baby Godzilla is present in both

scripts. I have a lot of respect for Son of Godzilla, and it is interesting

that Godzilla vs Mechagodzilla II seems to share that sentiment.

Godzilla, in this film,

resembles the Baby, but it is not as exaggerated as in Son of Godzilla (which

redesigned Godzilla to look closer to Minya). It is in subtle things, like the

positioning of a couple teeth when they both tip their head up to roar the same

way, and the more hunched-over stature of Godzilla that organically follows

from his previous film to film Heisei redesigns but also matches this new

version of Baby Godzilla. Aside from that, I just like the design, and I cannot

point to a specific reason that I like this design so much for him except that

he gets just shy of 27 minutes of screentime, much of it in daylight, to show

off this look.

The most major

difference from previous Heisei Godzilla incarnations is that Godzilla’s beam

is a lot more precise. Rather than aiming it down to bring it up to an

opponent, he will often just land it the first time (except for a few blasts in

the climax). I think, based on all of this other befuddlement, that this was

done to challenge the audience as much as possible. Godzilla is more dangerous

than he has ever been, but we understand him now for the first time. He has the

capacity to instantaneously target anything he wants, so when he chooses not

to, it also makes you wonder why he did not, and if he ever were to stop, could

we leave well enough alone? The viewer ends up stuck between two options rather

than being able to fully align with either side.

So, what is the answer

then: do we dirty our hands to defeat a sympathetic but rampaging creature with

G-Force, merely evacuate and hope to rebuild if Godzilla actually does stop

attacking this time or throw our hands up and chase down our own special

interests in the face of nuclear destruction as Kazuma Aoki does? That drama is

where Godzilla, the nuclear allegory, and Heisei Godzilla, the antihero,

operate best. Godzilla 1984 also had some version of this where, in the climax,

two of our leads are carrying out the plan to dump him in a volcano, the other

two are just trying to survive Godzilla’s nuclear destruction, and a homeless

man enters the story to decadently feast in the chaos as a third option for

what the natural human response to this crisis would be. (The homeless man is

actually a decently complex character; I just don’t have time to get into it

here.)

Chapter

Four - Conclusion or How I learned to stop worrying and rate this film an 8 out

of 10

I began this review

touching upon the history of Godzilla’s reinterpretations and what they mean if

you keep one eye trained on the original film. Godzilla is an icon because of

nuance and meaning where it was unexpected. Why would anyone expect Godzilla,

the villain of the piece, to be a sympathetic character that is as unfairly

destroyed as its victims? Why should anyone predict that Dr. Serizawa, the one

man with the knowledge to defeat Godzilla, is so deeply disturbed about his

miracle weapon he would rather kill himself than see it used again?

I am of the opinion, open to hearing contrary ones, that Mechagodzilla should not be some cheap sadistic alien knockoff no matter how cool the 1974 Mechagodzilla was but instead a deeper thematic foil to Godzilla. Ghidorah can have that role, but the more important facet of their rivalry is that they are always on opposing sides no matter what those sides are (Ghidorah as a good guy worked well in Godzilla, Mothra, King Ghidorah Giant Monsters All Out Attack 2001, as did the aforementioned heroic Mecha King Ghidorah). But Mechagodzilla is literally a human or at least humanoid-created Godzilla, and that carries so much subtextual complexity based on what Godzilla is and how humans created him, just less intentionally so. When Godzilla crosses between anti villain and anti hero, it is so much more interesting to have this shadow version do the same.

In Godzilla Against

Mechagodzilla, Mechagodzilla is reimagined to be the original Godzilla

unnaturally preserved into a new heroic being, and the normally destructive new

Godzilla gets a somewhat sympathetic streak due to the implicit familiarity of

his opponent, but, whereas, Kiryu (Mechagodzilla) resists his dark impulses,

Godzilla proper falls into them, needing to be stopped.

In Godzilla: City On The

Edge of Battle (though I despise that film and trilogy), Godzilla and

Mechagodzilla both took over their sections of Earth through mirrored means,

and choosing either one over the other turns out to be just as self destructive

in different ways for lead Haruo Sakaki.

And finally in Godzilla

vs Kong, Godzilla seemed to be slipping into a villainous role due to decreased

proximity to the goals of humans, while Mechagodzilla emerges as a villain due

to increased proximity to humans but really takes off for a rampage when it

divorces itself from human input and the remaining humans default to Godzilla’s

side, vindicating him.

But none of this

matters. We are talking about Godzilla vs Mechagodzilla II and how it executes

the complicated morality of rooting against the monster we built to defeat the

monster we accidentally started rooting for. I have argued for its merits, and I

spent less time arguing the flaws because I see less evidence of them.

It is important that you

understand this: when it comes to ranking and reviewing media, there are three

distinct areas you are sure to eventually disagree with me. 1. The flaws and

merits we notice. 2. Our evaluation of the severity of those flaws and merits.

3. How we compare these flaws and merits to those found in other relevant

media.

Perhaps you are the kind

of person that cannot fathom wasting money on one giant mech when you could

make a Super X armada and will not listen to any symbolic justifications

(Mechagodzilla as shadow Godzilla) or vague implicit ones (the head and shock

anchors of Mecha Ghidorah are the stimulus tech, how in the hell would they put

those into Super Xs?). In that case, the poorly fleshed out but ever more

reasonable single gauntlet of Project Powerhouse in Godzilla x Kong will make

more sense to you.

As I see it, Godzilla vs

Mechagodzilla II is a darn fine entry encompassing some of the best ideas of the

Heisei series. Execution is where it falls a little short. While I primarily

argue in favor of Aoki as the lead, more relevance given to his pteranodon

enthusiasm could only have improved the script. If Godzilla Minus One is a 10

out of 10 for instance, how much lower would it be if Shikishima’s kamikaze

background did not play into the final confrontation? Omae, as a very

unscientific and quickly irrelevant Professor, also is a bit of a dud in this

series of great scientist characters (Doctors Yamane, Serizawa, Mafune, and

Shirigami to name a few).

We here at Plan9Crunch

have a blog, podcast, YouTube channel, and TikTok page. If you enjoyed this

analysis, feel free to check out any of our other content, and Happy (now

belated) Godzilla Day.

Links to Godzilla

focused Plan9Crunch articles and videos below:

https://planninecrunch.blogspot.com/2023/06/review-godzilla-versus-kong-2021-remake.html

https://planninecrunch.blogspot.com/2014/03/godzilla-is-on-this-authors-mind.html

https://planninecrunch.blogspot.com/2021/12/godzilla-2000-review.html

https://planninecrunch.blogspot.com/2010/02/godzilla-versus-monster-zero.html

https://planninecrunch.blogspot.com/2024/06/a-nuanced-deconstruction-of-godzilla-x.html

https://planninecrunch.blogspot.com/2024/06/part-two-nuanced-deconstruction-of.html

https://planninecrunch.blogspot.com/2024/07/part-three-nuanced-deconstruction-of.html

https://youtu.be/yV6i2xX0pf4?si=Nu9RWsP5k6CbT68H

https://youtu.be/1HMV1hMPgzs?si=1Iip-2qfPxDe6G_B

https://youtu.be/pSosxtg51oM?si=CoDIwTko6C5N5DCY

https://youtu.be/AI_FMxtTlIk?si=EA51lODIQp2LUVr1

No comments:

Post a Comment